If you ask whether there is any evidence that the Israelites were ever in Egypt, most if not all skeptics—and scholars!—would answer without hesitation, “No, there is not.” Most Christians would hesitate to answer at first, but even those who we believe in the historicity of the biblical narrative would for the most part fail to cite specific evidence that lends credence to this key biblical account. Even more so, if you ask if we have any evidence that Moses was a historical character or that he ever existed, more emphatically this time, critics would quickly assert that such evidence does not exist; most Bible-believing Christians would say that such evidence may exist but they don’t know what it would be.

While most churches teach and preach on the message of Christ’s gospel every Sunday morning, a precious few, if any, preach on the historical reliability and accuracy of the word of God. Many claim that it should not be our emphasis as Christians to cite evidence for what we accept by faith to be true. After all, what is really important is that we “just believe,” right? But if these key events that the Bible claims to be historical never happened, what would that do to our faith? Would not that mean that our faith as Christians is based on fiction and lies? This is why the secular world is particularly targeting the earliest accounts found in the Bible with doubt and skepticism. If the devil can get you to believe that “In the beginning God did not create the heavens and the earth” or that the Israelites never crossed the Red Sea, he will also get you to believe either that Christ was not crucified—as Islam for example teaches—or that the dead body of Jesus is still lying in one of Israel’s tombs to this day waiting to be discovered! If you look around you, you will readily see that this is precisely the devil’s strategy from the beginning of creation. He distorts divine truth and gets you to believe that “in the day you eat of it, you will not surely die!” (compare Genesis 2:17 and 3:4).

In this article you will find out that there is more to the story that those “No” or “I’m sure it exists but I don’t know what it is” answers regarding Moses’s presence in Egypt, exactly as the Bible teaches. Admittedly, I am not an Egyptologist or a biblical archeologist, but being a Christian Egyptian myself, I find ancient Egyptian history fascinating, especially as it relates to the Bible.

Recently I came across a few magazine articles that suggest that a little known figure in the Egyptian history may in fact be the biblical Moses. At first, I was skeptical but then I started to investigate things myself. Before you dismiss these claims, let me share with you the highlights of these intriguing archeological finds.

Establishing the Timeframe

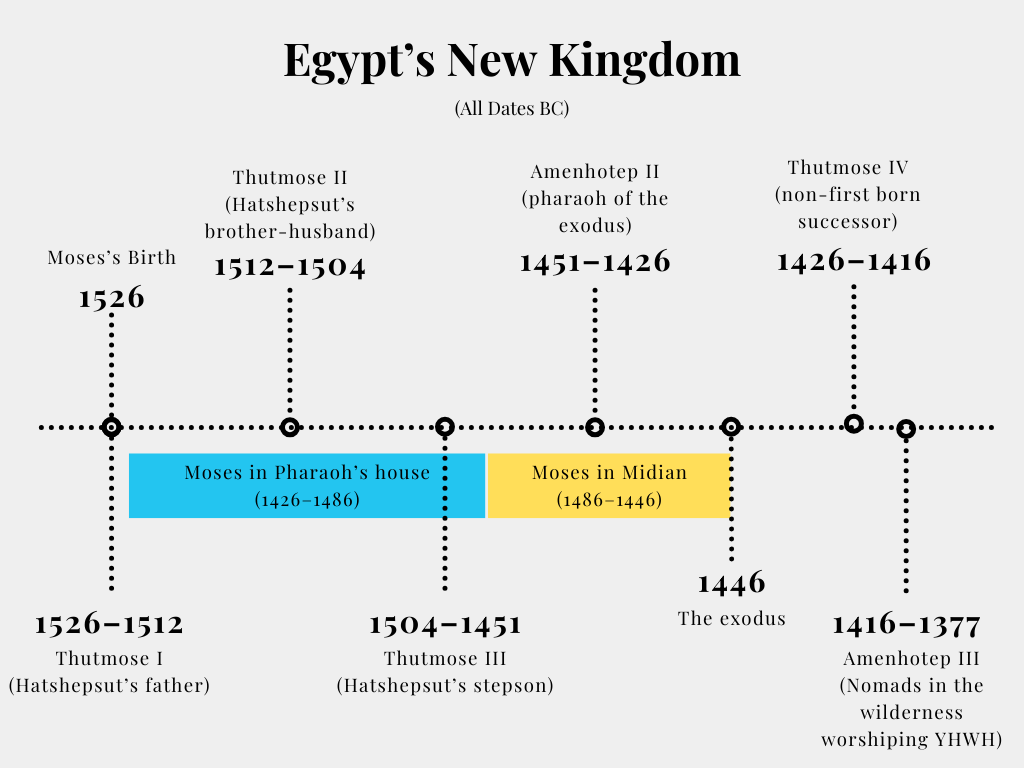

First, we need to establish some time markers in Egyptian history and how they parallel key biblical milestones. The Bible asserts that “in the four hundred and eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the LORD” (1 Kings 6:1). I realize that there is much scholarly debate over this timeline and whether these verses should be taken literally. But I believe that the Bible must be taken literally whenever the context does not suggest otherwise. Therefore, this verse places the Exodus in the year 1446 BC, since the building of the temple is widely accepted to have started in 967 BC. This aligns well with Jephthah’s claim that the Israelites had occupied Heshbon and Aroer 300 years before his time (Judges 11:26). Both of these cities are on the eastern side of the Jordan River in the land of Amorites. The Israelites conquered both of these and the surrounding areas at the end of their 40-year wilderness sojourn and right before they entered Canaan. Jephthah, who was one of Israel’s judges, lived around 1100 BC. This would put the conquest of Canaan sometime in early 1400s BC, approximately 40 years after their exodus out of Egypt.

Since Moses was 80 years old during the exodus, this means that he was born in 1526 BC (this chronology can be readily established by comparing various Scripture references such as Exodus 7:7; Numbers 14:33; Deuteronomy 29:4; 34:7). When these chronological markers are cross-referenced with Egyptian history, we find some interesting parallels.

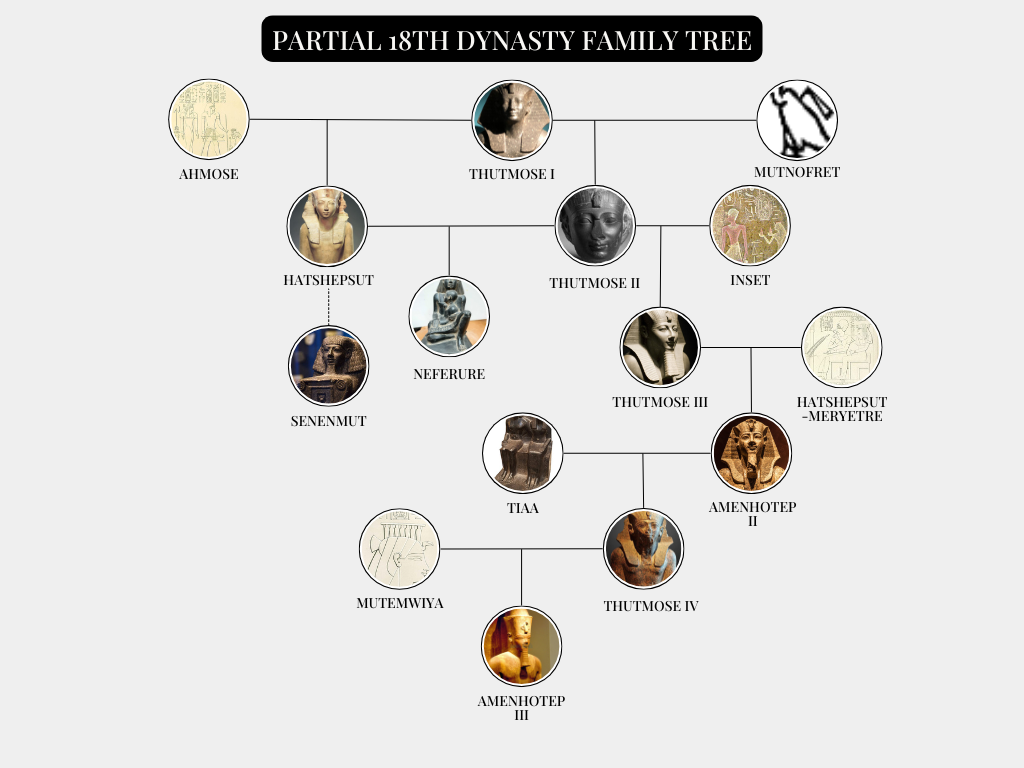

In the time period established above and working our way in chronological order from the older to the more recent, we encounter Thutmose I, whose reign was known for undertaking massive building projects in which slave labor was used extensively to build mud bricks using straw. Sound familiar? Exodus tells us that the Hebrew slaves were subjected to forced labor to perform this exact task before Moses was born (Exodus 1:13). I included a partial family tree below that includes the key figures, relevant to our chronology.

Thutmose I had a daughter named Hatshepsut. He also had a son named Thutmose II, but from a concubine this time. According to this chronology, Hatshepsut would be pharaoh’s daughter who took baby Moses from the Nile and raised him in her household as one of her own during the reign of her father, Thutmose I (Exodus 2:1–10). To ensure that his throne would stay in his family line, Thutmose I arranged that Hatshepsut would marry her half-brother, Thutmose II. As a result of this marriage, Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter named Neferure. But Thutmose II also had a son from a concubine. His name was Thutmose III. Due to Thutmose II’s illness, he died prematurely when his son Thutmose III was about two years old. His widow, Hatshepsut, assumed the throne of Egypt for about twenty-two years, becoming one of Egypt’s greatest pharaohs. She was one of Egypt’s most famous queens along with Nefertiti and Cleopatra. She reigned over Egypt until her stepson, Thutmose III, ascended to the throne. He was one of Egypt’s longest reigning kings (about 54 years) and among one of its greatest pharaohs. He was likely the pharaoh of the enslavement and oppression, during whose reign Moses killed the Egyptian and fled to Midian (Exodus 2:11–15). This aligns with the biblical account that as Moses lived in Midian, “During those many days the king of Egypt died” (Exodus 2:23). This biblical note suggests that whoever the pharaoh was during this time, he reigned over Egypt for an unusually long period of time. We find an additional testimony of this by Stephen in the book of Acts. He says, “Now when forty years had passed, an angel appeared to him in the wilderness of Mount Sinai, in a flame of fire in a bush” (Acts 7:30). Putting these two verses together it becomes evident that whoever the pharaoh of Egypt was during Moses’s stay in Midian, his reign had to be 40 years or longer.

Interestingly, Thutmose III was succeeded by Amenhotep II, who was not a firstborn pharaoh. Amenhotep II’s successor was Thutmose IV. He too was not a firstborn pharaoh and his ascension to the throne took place in mysterious circumstances and his reign was short—ten years or less. Why is this important? It is a well-established tradition in Egypt, as in most other kingdoms both past and present, that the heir to the throne is the king’s firstborn son. If the firstborn dies before the king, the next eldest living son typically inherits the throne. When we carefully examine the narrative in Exodus, we realize that the tenth plague killed all the firstborn males in Egypt in both man and cattle. If the pharaoh of the exodus himself was a firstborn king, he would have died in the plague. But we know that pharaoh himself did not die in the plague. Instead, it was his firstborn son who did (Exodus 11:4–5; 12:29–30). Thus, whoever the pharaoh of the exodus was, he could not have been a firstborn son, and since his firstborn son died in the plague, his successor could not have been a firstborn son either. Thus, we are looking for two consecutive pharaohs in Egypt’s history both of whom were not firstborn pharaohs. The first would be the pharaoh of the exodus, and the second would be his successor.

We find this exact sequence in Amenhotep II and his successor Thutmose IV. None of them were firstborn pharaohs. This suggests that Amenhotep II is likely the pharaoh of the exodus. But since this is a hotly contended issue, let me just add that we have a testimony from Manetho, an Egyptian historian from the 3rd century BC, who names the pharaoh of the exodus “Amenophis”—the Greek rendering of the Egyptian name “Amenhotep”!

During Amenhotep II’s reign the practice of building bricks from mud and straw was noticeably expanded—precisely as we read in Exodus 5:10–14. Intriguingly, the burial chamber of Amenhotep II’s right-hand man Rekhmire is filled with paintings depicting Asiatic (Semitic) slaves making bricks from mud and straw.

Finally, we arrive at Amenhotep III. He was the successor of Thutmose IV (Amenhotep II’s successor). During Amenhotep III’s reign we find a unique reference to nomads living in the wilderness worshiping a God by the name of YHWH. This suggests that Amenhotep III was the pharaoh during the 40-year sojourn of the Israelites in the wilderness of Sinai.

The timeline below provides a succinct overview of the succession of pharaohs during this period known as Egypt’s 18th dynasty.

Now that we have established the timeframe in which these biblical events are likely to have taken place, we will move right along to explore who our Moses candidate is. To this intriguing endeavor we will devote the remainder of this article.

Meet Senemut

In the preceding section of this article we laid the foundation for our investigation and identified the time period in Egypt’s history in which the exodus most likely took place. In the following section, we will explore one of the most intriguing and least known characters in Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. As you will see in our investigation below, the major milestones of his life bear a remarkable resemblance to that of Moses, leading me to believe that he is either the biblical Moses or someone who has a life/career unusually similar to Moses. His name is Senenmut (or Senmut).

He is introduced in the Egyptian records as a man of common origins with no royal ancestry. We know that he rose to prominence in Egypt until his mysterious disappearance in the mid 1480s BC. Despite his prominent position in the royal courts of Egypt, Senenmut’s parents are identified as peasants of no notable descent. More interestingly, this individual had a distinguished career of fighting as a high-ranking military officer in the Egyptian army against the Ethiopians (the land of Cush). This last detail, while seemingly insignificant, is particularly interesting as it relates to the biblical Moses.

The face of Senenmut, one of the most intriguing figure in Egypt's 18th Dynasty

For one, the Bible records a curious mention of Moses marrying a Cushite woman (Numbers 12:1). But more significantly, although the Bible is void of any mention of Moses’s military career prior to his escape to Midian, historians of that period, such as Josephus, speak at length of his expeditions in Cush (see Antiquities of the Jews 2.10). This is not surprising considering Moses’s later military campaigns against the Amalakites; Sihon, king of Amorites; and Og, king of the Bashan (Exodus 17:8–16; Numbers 21:21–35). Given that the Israelites at their initial departure from Egypt had no military experience, their leader needed to possess the military finesse sufficient to guide them through their initial exploits. The book of Exodus records this interesting note: “When Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near. For God said, ‘Lest the people change their minds when they see war and return to Egypt’” (Exodus 13:17). It shows how inexperienced the Israelites were initially as they departed from Egypt.

We also know that this person was incredibly close to the queen-mother, Hatshepsut (see the first section of this article in which we explored the likely timeframe/dynasty in Egyptian history where the exodus events more probably happened). His very name reveals his special relationship with her. Senenmut signifies “mother’s brother.” If Hatshepsut was indeed who snatched Moses from the waters of the Nile and raised him as her own son, one would expect to find evidence of this special bond. This is reflected in the “mother” reference in Senenmut’s name. Being the queen pharaoh of Egypt, she would also be considered a “brother” to another high-ranking member of the royal family even if by adoption. Thus, this odd combination of titles represented in his name seems all but fitting.

His relationship with Hatshepsut’s own daughter, Neferure, is also telling. First, we know that he tutored her daughter. Second and far more important, he is portrayed in multiple statues holding Neferure. This is uncharted territory in ancient Egyptian art since non-royalty were never allowed to touch kings, queens, or any other members of the royal family, let alone be depicted doing so. Senenmut is the only example we know of where a person from a non-royal origin is portrayed holding one of Egypt’s future queens. This would not be surprising, however, in Moses’s case given that he would be effectively considered Neferure’s brother by adoption. Of this unusual contact with royalty we find at least five distinct portraits of Senenmut.

Thus far, we have not explored how Senenmut may very well be the biblical Moses. After all, everything we know about him does not necessarily point to any major events in the Bible. Are there deeper connections that associted Senenmut with Moses?

Senenmut portrayed holding Neferure, Hatshepsut’s daughter

Similarities with the Biblical Moses

Senenmut has no record of marriage or offspring. This would be quite unusual if he were a member of the Egyptian royal family by lineage. But it does match the biblical account of Moses, for we know that Moses’s first wife was Zipporah, the daughter of Jethro, the priest of Madian. The fact that Senenmut was not married has led to widespread speculations regarding the true nature of his relationship with the queen-mother, Hatshepsut, and helped perpetuate theories that they were lovers. But these speculations have been long debunked by historians and Egyptologists alike.

Another interesting element related to the life of Senenmut comes in the form of his architectural skills. Egyptian records show that he was the main architect of Hatshepsut’s famous mortuary at el Deir el Bahary (Arabic for “the western monastery”). I remember visiting this architectural wonder with my family on a trip along Egypt’s central and southern Nile basin when I was about seven or eight years old. It is situated on the edge of the Nile just west of Luxor (hence the name). It is undoubtedly one of the architectural wonders of ancient Egypt in terms of its sheer size and complexity. This architectural ability is what one would expect of Moses, who later oversaw the construction of the tabernacle of the LORD in the wilderness. Intriguingly, Moses built an altar to the LORD with twelve pillars representing the twelve tribes of Israel. This pillared construction resembles the design of Hatshepsut’s mortuary.

Hatshepsut’s Mortuary West of Luxor

As it was the custom for all high ranking Egyptian officials of the time, Senenmut built a tomb chamber for himself. Inexplicably, it was never finished and its site was suddenly abandoned with the workers’ tool left inside! Even more peculiar, Senenmut himself was never buried in that tomb (keep in mind that grave robbers do not steal dead bodies or bones since they have no value to them—they only steal valuable belongings found inside the graves). Egyptian records are void of any explanation of his whereabouts after this point in Egypt’s history. Amazingly, Senenmut’s disappearance is dated to the year 18/19 of Hatshepsut’s 22-year coregency with her son Thutmose III. As seen in the timeline shown in the previous section, her reign began around 1504 BC. The 18th year of this reign would be 1486 BC, the 40th year of Moses’s life when he would have fled to Midian! Ready for what is even more intriguing? Read on!

Inside Senenmut’s empty tomb, a copy of a literary epic titled The Story of Sinhue was found. It dates back to the 12th dynasty of Egypt (Senenmut and Hatshepsut belong to the 18th dynasty). In that epic is the intriguing account of Sinhue who fled Egypt from the face of its pharaoh and went to live among the bedouins in the Levant region and married the daughter of one of their chiefs! The Levant region comprises Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel. This region is located just north of the land of Midian in northwest modern-day Saudi Arabia. Again, sounds familiar? The Bible tells us that Moses went to Midian, just south of the Levant, and married Zipphorah, the daughter of Jethro, one of the chiefs of Midian! (Exodus 2:15–22). Some Egyptologists believe that after he fled Egypt, Moses followed the epic of Sinhue, having been influenced by what he had read in it. Could all this be just a coincidence? I will let you form your own opinion but I do not believe so.

Conclusion

Senenmut’s story ends with the desecration of his tomb. His would-be sarcophagus had been vandalized and broken to pieces. Interestingly, it was by the order of Amenhotep II that Senenmut’s and Hatshepsut’s images and names were removed from most Egyptian monuments. Thankfully, this effort was not all successful, for many of Senenmut’s statues survived. But again, when we cross-reference these events with biblical history, we can readily see that if Amenhotep II was indeed the pharaoh of the exodus, this effort to erase Moses’s existence from the Egyptian records would be all but expected. Given that she was his adoptive mother, Hatshepsut’s records would be the object of a similar effort. This is precisely what we would expect to find in Egyptian records if the events recorded in the Bible truly happened.

In conclusion, while no one can provide irrefutable proof of Moses’ identity in Egyptian history or confirm the Israelites’ presence in Egypt beyond all doubt, the available evidence is undeniably compelling. In my opinion, it stands on par with other historical events that are widely accepted today, such as the historicity of Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar. The more I study biblical history and archaeology, the clearer it becomes that the level of scrutiny and skepticism applied to the Bible far exceeds that which is commonly applied to any other historical text. No one alive today witnessed Julius Caesar cross the Rubicon, yet most historians accept it as fact based on the reliability and sufficiency of the evidence. Similarly, many biblical events, both in the Old and New Testaments, are supported by equal or greater amount of evidence. Yet skeptic historians and archaeologists often apply a different standard to the Bible. But why does this double standard exist? Think about it for a minute. If Christianty were true—and it is indeed—the devil would not aim to shed doubt on the epics of Alexander the Great, the conquests of Julius Caesar, or the writings of Aristotle. Why not? Because the Bible is the only book that can change lives if believed in. Neither Greek philosophy nor the history of Rome can do that.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Eames, Christopher. “Is This Moses?” Let the Stones Speak, March-April 2024.

Eames, Christopher. “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?” Let the Stones Speak, March-April 2023.